THE 19TH CENTURY SOLAR ENGINES OF AUGUSTIN MOUCHOT, ABEL PIFRE, AND JOHN ERICSSON

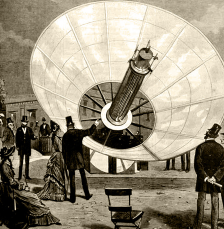

Augustin Mouchot taught secondary school mathematics from 1852-1871, and during this time he conducted a series of experiments in the conversion of solar energy into useful work. His proof-of-concept designs were so successful that he received support from the French government to continue the research full-time. His work was inspired and informed by that of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (who had constructed the first successful solar oven in 1767) and Claude Pouillet (who invented the Pyrheliometer in 1838). Mouchot worked on his most ambitious device in the sunny conditions of French Algeria and brought it back for demonstration at the Universal Exhibition in Paris of 1878. There he won the Gold Medal, impressing the judges with the production of ice from the power of the sun. Unfortunately, the falling price of coal meant that Mouchot’s work would soon be found unnecessary and his funding was cut. His assistant, Abel Pifre, would continue his work, however, and demonstrated a solar powered printing press in the Jardin des Tuileries in 1882. Although that day it was cloudy, the machine printed 500 copies per hour of Le Journal du Soleil, a newspaper written specially for the demonstration. Meanwhile, the great inventor and engineer John Ericsson had decided to do similar research. His work on solar engines spread the 1870s and 1880s. Instead of using steam, he used his version of the heat engine, a device that would work very successfully when powered with more standard fuel sources such as gas.

From Paul Collins’ 2002 essay The Beautiful Possibility:

“You will probably be surprised when I say that the sun-motor is nearer perfection than the steam-engine,” [Ericsson] wrote one friend, “but until coal mines are finished its value will not be fully recognized.” He calculated that solar power cost about ten times as much as coal, so that until coal began to run out, solar power would not be economically beneficial.

But this, to him, was not a sign of failure—there was no question that fossil fuels would run out someday. The great engineer continued an unshakeable belief in the future of solar power to his last breath; he had set up a large engine in his backyard and was still working on it when he collapsed in early 1889. Though his doctor made him rest, Ericsson could not sleep at night: he complained that he could not stop thinking about his work yet to be done.

Both Mouchot and Ericsson had an understanding that the sources of coal, the predominant fossil fuel of the time, would eventually finish. And while, new discoveries of petroleum and natural gas have extended our inexpensive access to energy. 140 years later their predictions came true. For the knowledge behind the proof is still as valid today as it was then—nothing that is limited can last forever. These inventors were so far ahead of their time, it is almost scary.